Architecture

Modernism: How The Principles Developed - A Brief History

The Beginnings and Development of the Modern Movement in Europe and the United States

By Robert Mosher, FAIA

The Modernist Movement in architecture had its beginnings with the development of democracy in both Europe and the United States in the Eighteenth Century, and the industrial revolution in the Nineteenth Century. These events set in motion cultural forces that opened the way for the Modernist Movement, which was dedicated to the improvement of social conditions and the rejection of traditional styles and planning procedures.

The Movement had its beginnings with architects in Holland, Austria, Germany and France, and soon found its way to America. In Germany, the idea of Modernism in architecture evolved from concepts being taught at the Bauhaus, a design and architecture school founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, in the city of Dessau.

In addition to Walter Gropius, a number of other European architects, including H. P. Berlage and Dudok in Holland, Otto Wagner in Vienna, and Eugene Flachat and Henri Labrouste in France, were impatient with the rate of progress being made in freeing architecture from the stranglehold of the influence of L’ Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In the early part of the Twentieth Century, these architects, and a group of sympathetic engineers and artists, were exploring ideas that set the stage for the revolution in architectural thinking following the establishment of the Bauhaus.

In defining the basic principle of the Bauhaus, and that of Modernism as it has since evolved, Robin Boyd, in his book, The Puzzle of Architecture, published in 1965, writes: “... Walter Gropius saw the futility of fighting the machine. Under him, the Bauhaus taught that the artist and the engineer and the technician must be brought together to work in mutual respect and understanding...

“... In the simplest terms, the Bauhaus’s architectural philosophy was that everything that man makes should follow nature’s rules and derive its form from the demands of its function and the character of the materials used. To achieve this, art and technique had to be fused into one, which meant that artists were best trained in the workshop, gaining familiarity with machines and materials...

“...The European vision was the more radical, spectacular and influential. It was also the more international because it spoke in the language of the machine instead of a native vernacular, however refined. In the European or Functionalist vision, construction was expressed openly and with relish, provided it was new construction characteristic of an industrialized era..”

Boyd also pointed out that: “...The issues really could be stated very simply and clearly. Modern architecture was attacking the old rule of the historical styles. It was also attacking the rules of composition: the concepts of proportion and symmetry. It was also attacking ornament. Ornament, in fact, was the symbol of the old that first had to be torn down by the new. Modern architecture then was campaigning on straightforward and uncomplicated principle. It was rational, clean, uncluttered. No dust traps. It was universal – hence an ‘International Style’...”

This defines Modernism as envisioned by the early European Modernists. Updating the definition to the present, the statement of purpose of the Congress of International Modern Architects (CIMA) states: ”We affirm that Modernism in architecture is not a style, but an attitude of mind.

This attitude toward architecture is characterized by a belief in the performance of service and problem solving, in the use of advanced building technologies, integrity of structures and materials, research and experimentation and, finally, a moral concern for our ecology and environment. We affirm the validity of a design process from the bottom up that skillfully integrates the above guidelines toward a resultant architectural expression in the spirit of the time.”

Conditions Which Gave Rise to the Development of Modernism In the United States:

In the United States, the years following World Wars I and II brought rapid changes in the social, political, and economic lives of all levels of American society. In response to these changes, architects began to address the issues of social reform, freedom of choice, and equality of opportunity for all of the people of our country. One of the most significant results of the Modern Movement was that the benefits of the work of contemporary architects became more accessible to a greater segment of the population.

The basic principles of Modernism, which are rationality and simplicity in resolving design concepts, and the honest expression of the nature of building materials and their structural quality, resulted in creating a new freedom from the restrictions imposed by tradition. This greatly aided architects and builders in their efforts to meet the challenge of providing contemporary buildings for an ever-increasing mobile population. The automobile rapidly became a major factor in modern planning and remains one of our most serious unresolved urban design problems.

In addition, the vacuum in building construction, following the Great Depression and WW II, created a surge in building development following the War. Together with the introduction of new building materials, exotic metals, composites, plastics, advanced structural systems, and inventive new equipment and tools, this had a profound effect on the building industry. As these developments were in complete harmony with the principles of Modernist architects, they enthusiastically accepted them.

A fundamental change in our country’s demographics affected the ways that Modernist Architecture developed. This was a greatly expanded middle-class purchasing power and the migration of people from rural to urban employment. New forms of urban housing, to which Modernist principles could be applied, took into account their rural attitudes but were adapted to their new urban life-styles. The result was the expansion of suburbs and inner-city high-rise development. In addition to housing, other types of commercial, industrial and civic building-projects benefited from the application of Modernist principles so that Modernism became a key factor in the orderly development of post-war America.

Principles of Modernism in the United States

Modernism evolved in two distinct ways in the United States: the first, pursued by the Humanists, sometimes referred to as Organic Architecture, was an outgrowth of our own uniquely American culture. The second, advocated by the proponents of the International School, was a philosophy imported primarily from the Bauhaus School in Germany.

The Humanists:

The beginning intent of the Humanist architects was to create work that stimulated emotional responses in people when they experienced the built-environment, in contrast to their responding intellectually. As a result, the early Humanist architects in United States created an entirely fresh approach to the design of their buildings, which established the basis for what has become American Humanism.

Louis Sullivan was generally credited with being the father of the Humanists. However, H. H. Richardson of Boston, who had a profound early influence on Sullivan, probably deserves a share of the credit. Frank Lloyd Wright, who worked for and learned from Sullivan, further developed Sullivan’s principles in his own unique architectural philosophy. During that early period, Craftsman architects, including Henry and Sumner Green, and Bernard Maybeck in California, furthered the Humanists’ cause.

Humanists respect the nature of the building site and its microclimates, and design their projects to take full advantage of a site’s natural characteristics. To preserve them, they employ natural materials -- wood, stone, copper, etc. -- to express the innate quality of those materials and their inherent structural and practical fitness; they combine art and building techniques to create unity and harmony between the two; and they create their designs to avoid formalism.

The Internationalists:

The intent of Internationalist architecture is the fusion of science and life, attempting to unite art and industry, and bring them into daily life using architecture as the intermediary.

European architects, such as Walter Gropius, (founder of the Bauhaus and later head of the Graduate School of Design at Harvard,) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, ((head of the architectural school at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT),) and Marcel Breuer, (who became Gropius’ partner and taught at Harvard,) came to the United States, bringing with them the principles of the International-Bauhaus School.

Internationalists reject all forms of extraneous ornament, choosing to allow the building’s structure, functional joining and detailing of their buildings to provide visual refinement. They design their projects with clean, crisp lines -- uncluttered, simple forms that clearly express the building’s structure and the functions they house; they are careful to use their building-material palette -- metals, concrete, plastics, glass, etc. -- to clearly express the true nature of the materials and structural systems employed, and visually define the various elements of the building as a whole.

Architects Who Brought European Modernism to the United States

In 1914, the young Viennese architect, Rudolf Schindler, emigrated to the United States following his mentor, Adolf Loos, who had come here earlier. He was drawn directly to Chicago, and it was no accident that Schindler sought out Frank Lloyd Wright, who was well-known in Germany where Schindler had been a student in the school of Otto Wagner. Schindler soon joined Wright’s office. In 1920, after having worked with Wright for some six years, he came to Los Angeles to supervise construction of Wright’s Barnsdall House on Olive Hill. Wright, at the time, was in Japan building the Imperial Hotel.

Richard Neutra, also from Vienna, came to the United States in 1923. He had also been a student of Adolf Loos and had come under the influence of Otto Wagner. Neutra and Schindler first met in Southern California in 1924. They found they shared the dream of creating a modern architecture. In 1925, with the intention of forming a partnership, Neutra and his wife moved into their recently completed house with the Schindlers. Later, this house was to become famous as the King’s Row House.

However, because of fundamental differences in their approach to architecture, Neutra and Schindler parted company, each following his own philosophy -- Neutra to the principles of the Bauhaus, and Schindler to his own concept of architecture, based on the idea that buildings should express the true nature of the materials from which they are built. This was an idea he had inherited from Wright.

Schindler was also beginning to concern himself with new spatial issues, based on highly rational and efficient modular systems. The systems were intended to accommodate the standard American sizes of building materials, eliminating cutting and waste. Surprisingly, when viewed from today’s practices, this was a revolutionary idea far ahead of its time.

Both Schindler and Neutra remained in Los Angeles throughout their lives, each pursuing his own concept of a truly Modern architecture. Both succeeded in creating individual architectural vocabularies that have had strong influences on succeeding generations of architects.

When Walter Gropius came to the United States to teach at Harvard University in 1937, other Modernist European architects followed, including: Mies van der Rohe, to the Illinois Institute of Technology, and Marcel Breuer, who formed a partnership with Gropius that same year. These architects were joined philosophically by Alvar Aalto and Eliel Saarinen in Finland, Le Corbusier and Auguste Perret in France, Sven Markelius in Sweden, Peter Behrens and Eric Mendelsohn in Germany, and Eero Saarinen, Eliel Saarinen’s son. All of these architects were dedicated to the ideas of the Internationalists. It is of interest to note that it was in Peter Behren’s office in Germany that Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius met as young apprentices.

It should also be noted that the philanthropist, George G. Booth, brought Eliel Saarinen here to design the great Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, completed in 1941. In 1950, his son, Eero, established a distinguished architectural practice in Bloomfield Hills. Eero Saarinen died tragically on August 15, 1961, the day his office was scheduled to be relocated to a beautiful estate near New Haven, in Hamden, Conn.

Two additional Europeans who came to this country and achieved fame as Modernists were Paul Crey from France, and Louis Kahn from Estonia, both of whom taught at the University of Pennsylvania. Crey was the architect of the Folger Library in Washington, D.C., and Kahn of the renowned Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. Both men, throughout their lives, contributed Modernist buildings of great distinction.

The First Examples of the International Style in the United States

The earliest significant example of the International Style in the United States was in a high-rise office building, the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society Building. Robert Stern, Dean of the School of Architecture at Yale University, describes this project, designed by the American architects, Howe and Lescaze in 1932, as....

”not merely a filing cabinet of offices, but a collection of great public rooms including a dramatic escalator hall, a banking hall that is one of the great spaces of modern times, and a penthouse suite that has set a standard for corporate aeries ever since...”

The building was a major landmark of Twentieth-Century Modernism. In the 1980’s, it was successfully renovated to serve the Twenty-First century. This was significant because in recent times, the requirements of the business world have rendered buildings like this obsolete for office use, placing them in danger of being demolished.

However, because of its convenient downtown location, the brilliant planning of its public spaces, its valid structural system, and its potential adaptability to meet the needs of contemporary business travelers and tourists, it was remodeled into a successful hotel. The result is that an important historically significant building has been preserved. It represents not only a profitable business venture, but also an outstanding example of historic preservation in which both the property owners and the preservationists have achieved their objectives.

Historical Perspective – Early Development of Modernism in the United States:

The American Modernist Movement had its faint beginning, starting with the work of Henry Hobson Richardson, in the mid-1880’s. Richardson served as an early inspiration to Louis Sullivan in Chicago with his design of the Marshall Field warehouse store, which Sullivan described ”as an oasis in the midst of a desert of doubtfully sincere edifices.”

Following Richardson, it was Sullivan, his partner, Dankmar Adler and their Chicago contemporaries, William Le Baron Jenney, Holabird and Roche, D.H. Burnham, and Frank Lloyd Wright, whose work established what has become part of a great cultural heritage in America.

As early as 1900, Adler and Sullivan were designing forward-looking buildings such as the Carson, Pirie, Scott department store, and the restored and still widely used, Auditorium Building. In addition to the simplicity and clarity of structure and purpose inherent in those of the International Style, these buildings incorporated hints of Humanism in their integrated ornamentation and form.

In the introduction to Chicago’s Famous Buildings, edited by Arthur Siegel, Hugh Dalziel Duncan quotes Sullivan, who asked the question,

“What is the proper form for a democratic architecture, and what kinds of human relationships will be possible in this new architecture?”

He answered the first question by proposing that whatever the use of a building, its form must follow its function. Not a mechanical function, like a traffic flow, circulation of air, heating, lighting etc., but a human function. He thought that the architect must ask himself: how can I enhance the human satisfaction of acting within my building or the communities I design? If I design a house of prayer, how do I make prayer more significant? If I design a department store, how do I make shopping more pleasurable? If I design a factory, how do I make work healthy and pleasurable? If I design a tomb, how do I make the sorrowing family feel the serenity and peace of death as a memory of life? This is what Sullivan meant by his constantly repeated phrase:

“A building is an act,” and those ideas can well serve us as a satisfactory definition of humanism as we use now it in architecture.”

Frank Lloyd Wright and a distinguished group of architects who were also proponents of the architecture of Humanism soon followed Sullivan. This work contrasted with that of the International Style in that it relied less on conceptual intellectual analysis in arriving at architectural solutions, but employed natural materials, informal open planning, and less rigid forms.

Thus, in America, there were two Modernist schools of thought, each having developed from differing cultural influences. As the two movements rapidly evolved, young architects began to produce work reflecting both bases -- the warmth of the Humanists on the one hand, and the discipline and clarity of the Internationalists, on the other.

The Evolution of Humanism in American Architecture:

Throughout his long life, Frank Lloyd Wright, who died in 1958 at the age of 89, was a passionate voice for Humanism. During his career, he and his followers continued to produce work that reflected his distinctly original interpretation of Humanist principles. He defined these both in his executed work, which was extensively published and which received critical acclaim, and in his many published books and writings, the principal of which was, In the Nature of Materials, published in 1942.

He and his ideas attracted many strong and ardent supporters and followers. Also, and not surprisingly, there were a considerable number of detractors because his chosen lifestyle was not in keeping with the moral customs of the time. However, the negative aspects of Wright’s life are now largely forgotten as society has accepted, as normal, the behavior so widely criticized in Wright’s day. Today, his influence in architecture is still felt, especially among a growing number of young architects seeking a vocabulary in which they can believe.

During the early 1900's in California, in addition to Wright's ardent followers, a separate group of architects emerged who longed to work with simple forms and natural materials. Many believed in Wright's principles and were also influenced by aesthetic ideas coming from Asia, especially from Japan, as Wright had been.

Early Development of a Modern Regionalism in the United States

Modern regionalism, especially that in the Pacific Northwest, was relatively short-lived, spanning the time between the early nineteen hundreds and the advent of contemporary conditions, emphasizing rapid communications and personal mobility. All of this brought people and our diversified cultural identities into intimate and stimulating contact. This, for many, is an unfortunate aspect of our current architectural development as it tends to homogenize the built environment and diminish our individualism.

However, the sense of place – regionalism - did flourish, particularly during the 1930’s, -40’s and -50’s, with the results described below.

The Pacific Northwest:

Prior to and following World War II, the Pacific Northwest coastal areas developed their own regional character. In those years, Seattle and Portland were the ports of entry for most goods and immigration from Asia, so it was only natural that Asian culture would have a significant influences on the creative endeavors of the artists and architects of the region.

Two additional influences played major roles in affecting the regional character of the Northwest -- the tradition of the native wooden buildings - the Indian Longhouses - and the abundance of easily obtained timber.

However, the predominant influence came from Japan where, particularly in traditional residential design, modular planning, set by the dimensions of tatami floor-mats, established a disciplined rhythmic design. Japanese buildings, which were principally built of wood, expressed the nature of wood in a clear, logical, crafted manner.

Influenced by these examples, Northwest architects applied those guiding principles to their own work, creating a uniquely valid architecture that took into account the wet weather and often sunless days.

Also, there are those who give much credit for these results, in both the Pacific Northwest and the San Francisco Bay Area, to the quality of the education provided by west coast architectural schools.

Two of the many professors of architecture, through their teaching and their architectural practices, who had a profound influence on the young architects coming into the profession, were Lionel Pries, at the University of Washington, and William Wilson Wurster, at the University of California, Berkeley. These men had been classmates at the University of Pennsylvania and shared Humanist beliefs and the virtues of regionalism.

Following World War II in Seattle, in addition to Lionel Pries, a number of young architects followed the Modernist principles they had learned in school and to which they were devotedly committed: Ralph Anderson, Fred Bassetti, James Chiarelli, Henry Klein, Paul Hayden Kirk, Keith Kolb, Wendell Lovett, Royal McClure, John Morse, Robert Shields. Jack Sproule, Roland Terry and Burton Tucker. Much of their work survives today and is coming to be valued and preserved.

In Portland, John Yahn and Pietro Belluschi dominated the Modernist Movement, Yahn with his houses, and Belluschi with both his houses and wood churches. Later in his career, Belluschi went on to become Dean of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, following William Wilson Wurster.

The San Francisco Bay Area:

As early as 1886, beginning with only two wood-shingle and redwood houses and a church, designed by Joseph Worcester, a distinctly original regional Humanist architectural tradition began to develop. Willis Polk and Ernest Coxhead furthered the use of natural materials and the simplicity of form and construction. These three architects set the stage for Bernard Maybeck, who expanded on their ideas, designing a great many fine wooden houses and the Faculty Club at the University of California, Berkeley.

In 1910, Julia Morgan completed a church which, in their book, Building With Nature: Roots of the San Francisco Bay Region Tradition, Leslie Mandelson and Elizabeth Sussman describe as....

“Julia Morgan’s wooden St. John’s Presbyterian Church (2640 College Avenue, Berkeley, 1908 and 1910) followed the Bay Region tradition of domestically scaled churches; it appeared modest from the outside, its mass low to the ground beneath wide spreading gables. Yet the interior vertical lines and uncarved open beams again suggested the rural, open timbered barn....”

This building, together with the early houses described above, set the stage for what came to be revered as the San Francisco Bay Area Tradition. Other simple, rural buildings present in the area -- board and batten farmhouses and barns of the mid- to late-nineteenth century -- clearly expressed the essentials of good domestic architecture, and had an influence on the above-mentioned architects.

Many talented architects, inspired and encouraged by the early pioneers, followed: William Stephen Allen, Robert Anshen, Theodore Bernardi, Charles Warren Callister, Mario Corbett, Gardner Dailey, Vernon De Mars, Joseph Esherick, Robert Marquis, Charles Moore, Claude Stoller, William Turnbull, William Wilson Wurster, and many more, contributed to this remarkable development.

William Wilson Wurster was, like Maybeck before him, the dominant Bay Area figure in the 1920’s to the1960’s development of the tradition. Wurster designed rural houses built of wood, which recalled earlier ranch houses but were simpler and, in many ways, more sophisticated. Many of Wurster’s San Francisco city houses, unlike to those built in the Nineteenth Century, exhibited a sophisticated simplicity of detail, material use, and form, that came to define, for many, San Francisco’s domestic architecture.

The Bay Area tradition developed mainly as the result of the presence of a concentration of very talented architects schooled in the Modernist Movement, and the existence of well-informed, courageous and sophisticated clients, a combination of circumstances not often encountered.

In the United States, regionalism probably never again will be possible in the same way. Changes in cultural habits and the advent of practically instantaneous communications have dulled, to a degree, the ability of communities, as well as individuals, to express wholly independent thought and action, unaffected by outside influences and cultural pressures.

The Los Angeles Area:

Charles and Henry Greene, having served their apprenticeships in Boston, moved to Pasadena in 1883. In 1894, they designed their first house for a John Briener. In 1897, they moved into the Kinney–Kendall Building they had designed and built the previous year, and their practice flourished. In their architecture, they followed much the same path as their San Francisco counterparts, utilizing natural materials -- wood, brick and stone – using broad eaves joined to open pergolas and trellises, responding to influences from Asia, especially Japan. Their designs, both exterior and interior, showed a complete understanding of the nature of their material palette, clearly demonstrated by the fact that the houses that have survived retain most of their original beauty, tight carpentry and form. (See the Gamble House in Pasadena.) During their professional lives of some forty-six years, the brothers designed and built 133 buildings, of which 72 have survived, a fitting tribute to these two who contributed so much to the early California Modernist Movement.

Rudolf Schindler, as previously noted, began his practice in Los Angeles in 1921, pursuing Modernity until his death in 1953.

Richard Neutra came to Los Angeles in 1923 and built his now famous house overlooking Silver Lake in Los Angeles.

Frank Lloyd Wright, during the years 1923 to 1927, designed only six houses in America, five of which were built in the Los Angeles area. In these houses, Wright experimented with a standardized interlocking concrete-block system, the exposed faces of which were cast with a geometric pattern. When laid up in a wall, the result was a rich surface of light and shadow, another example of Wright’s expression of organic design.

Following World War II, Los Angeles attracted a great many young architects from both the Humanist and International schools, and some not committed to either but supportive of the movement away from the Beaux-Arts tradition. These architects found, in Southern California, a receptive audience for buildings appropriate to the forward-looking, progressive ideas and needs of a fast-growing population, intent on becoming the focal point of innovative developments.

John Entenza, a young editor and publisher, started “Arts and Architecture” magazine in 1938, which had soon established a line of communication between layman and the architectural profession. The magazine became the leader in winning the public to accept the concept of good design in the Modern vocabulary.

As a result of the Depression and the Second World War, during which little civilian building had taken place, a serious need had developed for new building construction, especially in lower- and middle-income housing.

In response to this vacuum, in January 1945, just seven months before peace was declared, Entenza announced the Case Study House Program, the purpose of which was to create an opportunity for young, enterprising and innovative architects, together with those manufacturers who made progressive products for the building industry, to design and build modest houses in the Modern vocabulary. The designs were to address Modernist principles in a fresh, new way. The architects who completed projects in the program were: J. R. Davidson, Spaulding and Rex, Nomland and Nomland, Rodney A. Walker, Thornton M. Abell, Richard Neutra, Wurster and Bernardi, Charles Eames, Eames and Saarinen, Raphael Soriano, Craig Elwood, Buff, Straub and Hensman, Pierre Koenig, Killingsworth, Brady and Smith, David Thorne, Ralph Rapson, Whitney R. Smith, Don Knorr, and Jones & Emmons.

The results established Modernism, not only in California, but also set a positive example for the rest of the country. During the same period, other Southern California architects such as A. Quincy Jones, John Lautner, Gregory Ain, Harwell Hamilton Harris, and Gordon Drake, devoted their creative lives to furthering the development of the Modern Movement.

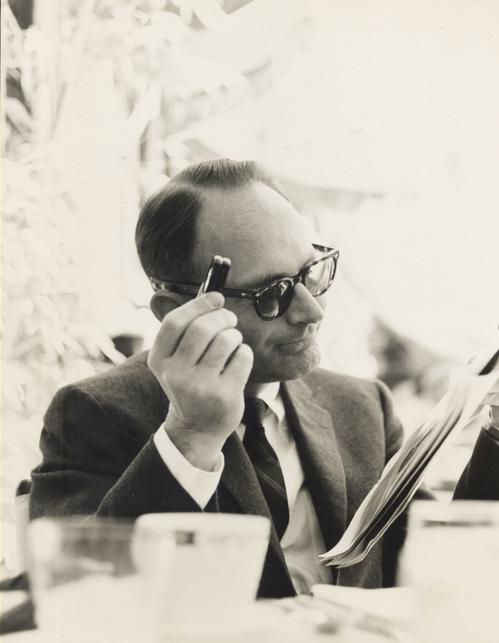

A. Quincy Jones opened his office in 1945, the day after his release from the U.S. Navy. In 1950, he formed a partnership with Fredrick E. Emmons and, in 1970, at Emmons retirement, he returned to sole ownership of the firm which terminated with his untimely death in 1979 at the height of his career.

During this entire period, he created a very personal practice, ranging from University Master Planning, tract housing, industrial and commercial design to residential design. In all of these diversified architectural activities, he brought a fresh, very original point of view, entirely his own but always in accordance with Modernist principles. His work was greatly influenced by the things he saw and learned during his extensive travels abroad, where he made endless sketches of everything there that affected him.

As Elaine Sewell Jones, one of the editors of A. Quincy Jones: The Oneness of Architecture, writes, “A. Quincy Jones’s place in architecture is assured by the humanism and beauty of his buildings, their environmental responsiveness and the enduring significance of the reforms he set in motion.

“Quincy was also an architect for whom drawing was a way of participating in a place, a form of visual notation. He believed in drawing as a communication of knowledge and emotion rather than as a precious commodity. In 1968 he wrote in the AIA Journal, ‘By sketching on a trip I enhance my ability to see and feel spaces’. He cherished those moments of a journey when he could return to his hotel room and finish the sketches started earlier in the day. One can well imagine how this generous and public man was nourished by these private times.”

Quincy was a student of Lionel H. Pries at the University of Washington. He was a brilliant and cultured man and his work often reflected the inspiration given him by his teacher and mentor, who taught him the joys and satisfaction of drawing and sketching as well as to regard architecture as a noble art. In 1960, speaking to a group of the AIA, Jones said,

“There is no unimportant architecture. Everything in the built environment affects people and, in turn, the world, whether it is good or not so good. The architect needs to look on his work as a way of seeking a balance between “our powers of thinking and our sense of feeling.”

John Lautner, throughout his thirty-five years of practice, evolved an architectural approach entirely his own, using a bold, strongly geometric, design vocabulary more often expressed in brilliantly formed concrete. His highly innovative and original design philosophy sets him apart from his peers and earned him the reputation for being an idealist, devoted to architecture as an art. He is quoted as having said,

“It seems to me, the Artist’s and Philosopher’s lifetime work is a search for Reality. Attempting the almost impossible – most Philosophers do with their lifetime work – trying to put into writing the essential basics of true life which are the same for everything, and, in my case, Architecture. Reality, as I see it, is the intangible essence of Truth and Beauty, timeless and universal in relation to man. Reality is my lifetime search to produce timeless joy-giving free spaces to fulfill ideally man’s needs – physical and spiritual, i.e. total.”

John Lautner did, indeed, fulfill his dream.

Harwell Hamilton Harris’s work was almost entirely residential and built in wood. Harris, much influenced by the Green brothers and the Japanese tradition, favored wood construction, often referring to his use of it as “clear carpentry.” By this, he meant relating every member of a structure to the next in a straightforward, natural manner so as to ensure that the entire structure would not only stay together and weather well, but also present a unified appearance throughout the life of the building.

Harris, like the Japanese, designed on the basis of a module, often of three feet, which, translated into plans, created a sense of order and serenity as one moved through his houses. More importantly, the rhythm of the plans carried the rhythm into the walls, soffit light panels, exterior trellises, and ceilings, giving the whole structure unity and a sense of being settled and serene. During a visit to one of his houses, the owner pointed out the way the sun’s shadow cast a pattern on a wall that was paneled with the same module as the trellis, which cast the shadow. I doubt that the owner ever gave a thought to the actual presence of the modular planning, but every day, he was aware and appreciative of the visual results.

Regrettably, there are many who believe that Harris never achieved the architectural recognition he deserved, having buried himself in teaching, which he much cared for and at which he was very successful.

The San Diego Area:

Early practitioners of the Modernist Movement in San Diego, who recognized the validity and appropriateness of the ideas being proposed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Bernard Maybeck, and Charles and Henry Greene, were Emmor Brooke Weaver, Irving Gill, and Hazel Waterman.

Later, during and immediately after World War II, Lloyd Ruocco, Sim Bruce Richards and an obscure designer/builder, William Kessling, set in motion the post-war growth of Modernism in the community.

Emmor Brooke Weaver was one of the early pioneers in San Diego to practice a brand of Modernism, similar to that of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Pasadena. There is really little known about Weaver except that he graduated from the University of Illinois, came to San Diego as a young man and practiced here all of his life, designing buildings in both San Diego and Los Angeles. Although he worked in a number of styles, he is principally known for his attraction to the work of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and his masterly houses were executed in that vocabulary. Weaver, like the Green brothers, demanded fine carpentry and, for that reason, he himself built many of his houses. Once, during a discussion, he explained that in order to keep the redwood boards being erected by his carpenters free from being stained by the oil from the carpenter’s hands, he provided each of them with clean cotton gloves daily. He also provided clean overalls. It was this kind of attention to detail that insured that the quality of the satin finish of the redwood was preserved.

Irving Gill was born in Tully, New York, in 1870. His antecedents emigrated from London to the U.S. in 1700. He grew up in Syracuse and worked there as a draftsman, later moving to Chicago. In 1891, he obtained employment in the office of Adler and Sullivan. It was there that he met and worked under the supervision of Frank Lloyd Wright. Sullivan advocated abandonment of the then current European Revival styles and endorsed the principle of organic architecture. Deeply influenced by the training he received in Sullivan’s office, Gill worked very hard there -- to the point where illness caused him to leave and, in desperation, to seek a new, healthier life in California. Thus, in 1893, he came to San Diego, and remained here until his death in 1936.

In some of his most influential work, Gill was responsive to the “Spanish Mission Style” that he found in the Southern California region. He extracted the essence of the Spanish style but transformed it into purely expressed forms, simplified and without ornamentation. Building in stucco, finished cast-concrete, and hollow tile when his clients could afford it, and wood-frame and stucco when they could not, his was an entirely innovative concept of design and construction. The La Jolla Woman’s Club, built in 1912/13, is an outstanding example of the pre-cast, tilt-up-slab method for constructing walls he strongly advocated and which proved to be successful.

Gill’s fundamental ideas were to simplify -- to eliminate unnecessary ledges, moldings, and recesses. The exterior of his buildings, pitched-roof or flat, in their form and detailing, were clear, concise, uncomplicated expressions of plain concrete or stucco. Window and door openings were only slightly recessed and without trim. All openings on the exterior were carefully aligned, located and spaced so as to present an organized composition. Where he employed arched openings, as in the case of The La Jolla Woman’s Club, they were true arches, properly proportioned in the tradition of their Spanish heritage, and an honest representation of the masonry construction they represented.

Gill alone, and together with his various associates and partners, designed about 311 projects. He had partnerships with William Sterling Hebbard, from 1896 to 1906, and with Frank Mead, in 1907. Gill died in San Diego in 1936.

At the end of the World War II, Lloyd Ruocco, who had worked for the Navy during the war, began to establish himself as the principle leader of a small Modernist group, many of whom had been stationed in San Diego with the armed services, and all of whom saw in San Diego, fresh architectural opportunities. As the construction industry began to adjust to peacetime conditions, Ruocco and his wife, Ilse, showing great courage when they designed and built a remarkable retail and office building located on upper Fifth Avenue.

They named this building the Design Center and it, with the University of California San Diego’s Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, set a standard of excellence for all Modernist projects in the community to follow.

Ruocco was a master of the use of natural materials: unpainted wood, stone, and brick were his palette. As with all Modernists, he employed glass extensively. However, in his hands, through the sensitive arrangement of the structure and architectural elements of his designs, the glass virtually disappeared. He loved and respected nature and the outdoors, and his work clearly demonstrated this respect.

In his role as a leader among the increasing number of young architects committed to Modernism, Ruocco took a strong position. Throughout his life, he arranged numerous meetings at The Design Center, where he led discussions, brought in inspiring lecturers, and set up exhibits of interest to people who longed to learn about Modernists ideas.

His wife, Ilse, also maintained a studio in the Design Center which showed all of the Modern furniture available at any one time, as well as providing a complete interior design service, when there was little else of its kind in San Diego.

Lloyd and Ilse Ruocco were truly inspirational and provided encouragement to those post-war architects who were fortunate enough to come under their influence.

Sim Bruce Richards was another architect who had his own, clearly recognizable architectural vocabulary. Throughout his architectural life, he pursued and refined his work, always staying true to the principles he had learned at the side of his mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright.

Richards career was devoted to two great passions, his family and his architecture. In 1984, the San Diego Museum of Natural History published a book entitled, Nature in Architecture, in which much of his work was illustrated with photographs and his drawings, which describe the natural beauty of his buildings, their shallow sloping roofs -- always with wide eaves -- their exclusive use of wood and brick masonry, and their rich, romantic, careful detailing. He said of his own work: “Good architecture is a sense of space and where to put it and how to break it apart.….. People say I’m an all-wood architect and I guess I’m comfortable with that reputation.….. There’s a false economy at work in most buildings that have walls of plaster or dry-wall. Anything you have to paint is false economy.”

William Kessling. The Great Depression and World War II nearly halted new construction. However, the La Jolla designer/contractor, William Kessling, built some remarkable, small, wartime houses, all on a four-foot module and with a post-and-beam construction system. The structural frame was in-filled with a four-by-eight-foot panel material consisting of a one-inch fiberboard covered on each side with a layer of one-eighth-inch asbestos board. These houses, though small, were well-planned, and utilized large panels of floor-to-ceiling glass which related the interior of the house with garden/terrace areas in a pleasant manner.

At the time that Kessling was building, few paid much attention to his work but in retrospect, his designs demonstrate progressive thinking and were surely significant examples of Modernist thought, far ahead of their time. Those few buildings that remain (and which have not been poorly maintained or altered beyond recognition) are prized by their owners and deserve to be preserved.

Either during or just after the war, Kessling moved away, with the result that he was not a factor in post-war San Diego Modernism.

A large group of enterprising young architects followed, contributing to furthering the ideals of the Modern Movement and pursuing their practices in accordance with its principles.

They include: James Alcorn, Gary Allen, Norman Applebaum, Wallace Cunningham, Ward Deems, Homer Delawie, Roy Drew, Russell Forester, Donald Goldman, John Henderson, Henry Hester, Edward Hom, Robert Jones, Kendrick Kellogg, Joseph Lancor, William Lewis, Frederick Liebhardt, Alphonso Macy, Paul McKim, Robert Mosher, Dale Naegle, Harold Sadler, Leonard Veitzer, Eugene Weston, III, and others.

Conclusion: The foregoing is intended to convey the sense and meaning of the Modernist movement in architecture. It recognizes many of the major architects who have followed their dreams of creating an architectural expression reflecting the true nature of the culture of the Twentieth Century. There are many more who have contributed to the wealth of modern work and who can take pride in their accomplishments.

Modernist Design Principles

The following criteria set forth, in general terms, the principles which identify Modernist architecture and which can be employed in evaluating projects as to their eligibility to be classified as being valid examples of Modernist Architecture.

I. Landscape and Site Design:

Modern garden design has evolved from the previous traditional concepts of formality and rigidity to fresh, new, expressions, reflecting the Modernist architectural attitudes and life styles.

In creating the modern gardens, the designers are free to develop new forms and combinations of textures, with the options of utilizing a wide variety of available plant and building materials. The fundamental factors in designing Modernist architecture also apply to designing the garden: meeting the clients specific needs, making the garden design complimentary to buildings, relating to land forms, and considering the microclimates and general weather conditions encountered at the site.

Modernist garden designs range from those generally defined as in the Internationalist style, with rigid, clean, mechanical layout and design, to the more basic, organic Humanistic style, with natural massing of materials and organization, as greatly influenced by the design philosophy of the classic Japanese gardens. The garden landscape includes the planting, hardscape, waterscape, and the land forms.

The following principles guide Modernist Landscape Design:

The Site:

The site includes the topography, the views, and the site forms and elements, which have great impact on both the structures and the garden. A thorough analysis should be taken of the site as part of the design. As they relate to other elements of the design, the decks, patios, courtyards, atriums, view vistas and corridors are carefully considered. Next to planting, they have the greatest impact on the design of the Modernist garden and should be given great importance when evaluating a design. Do the landscape and planted areas relate and flow comfortably and visually with both the interior and exterior spaces and with the land forms? Do the landforms enhance the livability of the site? Are critical views retained or enhanced? The site is complimented by a landscaping plan that incorporates vegetation plantings, hardscape, and sometimes, water features. Vegetation and planting areas are chosen for their orientation, water requirements, size and function, and how they complement the overall development and the human experience of the total.

Does the solution address the nature of these elements in its final development?

Microclimate:

The mild climate of Southern California encourages outdoor living activities and dramatic views are most important aspects of Modernist architecture. Does the design address and take advantage of the path of the sun and the wind patterns and the effect that adjacent structures have on the conditions?

Circulation:

Circulation includes the access to and from the site and travel through the site and its elements, allowing a design that works well with the site and its elements. Circulation that works well with the site elements and enhances the function of the site is essential to the landscape design's success. Does the design provide clearly defined and comfortable pedestrian circulation for both inhabitants and visitors? Are automobiles and service vehicles provided for in a convenient but unobtrusive manner?

II. Architectural Design

Planning for traditional designs was restricted to well-established forms and spatial relationships. The architect was restricted in his creativity to conform to these pre-established rules. Modernism changed that and allowed the architect the freedom to create spaces that directly and functionally met his client’s needs. It related those spaces to one another in an orderly and appropriate manner to reflect the life-styles and activities of the people for whom they are designed, without the restrictions of stylistic restraints.

The following principles guide a Modernist building design:

Building Materials and Structure:

In Modernist architecture, the straightforward use of the building materials and structural systems selected for the project, form the basis of the design. These elements are never disguised behind phony, false fronts or traditional detailing. Each material speaks for itself and the structure is clearly evident and expressed.

Integration of Interior and Exterior:

Interior and exterior spaces become integrated by means of the use of large areas of glass, most often in the form of floor-to-ceiling sliding doors. This simple device facilitates the easy flow of the spatial experience as well as people, from the interior rooms to the garden areas, creating a new and freer relationship between the two. It also has the effect of creating a sense of greater space for interior rooms as the gardens visually became a part of the interior. Furthering the integration of the interior and exterior, the same or similar paving and plant materials are utilized in both areas, making the transition between the two more transparent.

Interaction with Natural Environment:

Natural lighting and ventilation, other than that provided by doors and windows, is often integrated into the design in the forms of clerestory windows and skylights. These, in turn, integrate with the structure so as to create a unified whole. The building’s orientation and openings accommodate sunlight and the natural air currents of the site.

Broad eaves, trellises, screens and fences are provided where they serve functional purposes in controlling sunlight and wind, provide privacy, and protect the building from the elements. Ventilation systems may also be used to obtain better interior environmental comfort.

Conclusion:

In deciding whether a project qualifies as a valid example of Modernist work, the project should be judged on the basis of how well it meets the criteria enumerated above.

Modernist architecture, as defined herein, has reached a point where it is recognized as being a valid style, and is valued as such. There is interest in preserving the best examples of Modernist work and it is hoped that this definition of Modernist architecture will be of value to those who pursue the subject.

To learn more about Modernism in architecture, please refer to the following publications, which provide visual descriptions of Modernist elements to aid in recognition and evaluation of projects.:

- American Design -- The Northwest, by Linda Humphrey and Fred Albert

- Architecture As Space, by Bruno Zevy

- Blueprints for Modern Living: History and Legacy of the Case Study Houses

- Building With Nature: Roots of the San Francisco Bay Region Tradition, by Leslie Mandelson Freudenheim and Elizabeth Sacks Sussman

- In The Nature Of Materials, by Frank Lloyd Wright

- Irving J. Gill, Architect, by Bruce Kamerling

- Process And Expression In Architectural Form, by Gunnar Birkerts

- Structures, by Pier Luigi Nervi

- The California Bungalow, by Robert Winter

- The Man-Made Environment: An Introduction To World Architecture and Design, by Calvin C. Straub

- The Oral History Of Modern Architecture -- Interviews with the Greatest Architects of the Twentieth Century, by John Peter

- The Puzzle of Architecture, by Robin Boyd

- Toward a New Regionalism -- Environmental Architecture in the Pacific Northwest, by David E. Mill

- Five California Architects, by Esther McCoy

- The Second Generation, by Esther McCoy

Have an idea or tip?

We want to hear from you!

email hidden; JavaScript is required

Architecture

Modern San Diego Stuff For Sale

Architecture

Streamline Modern(e) San Diego

Architecture