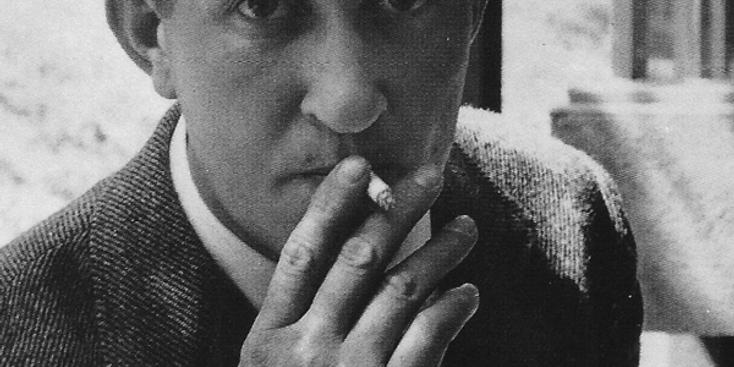

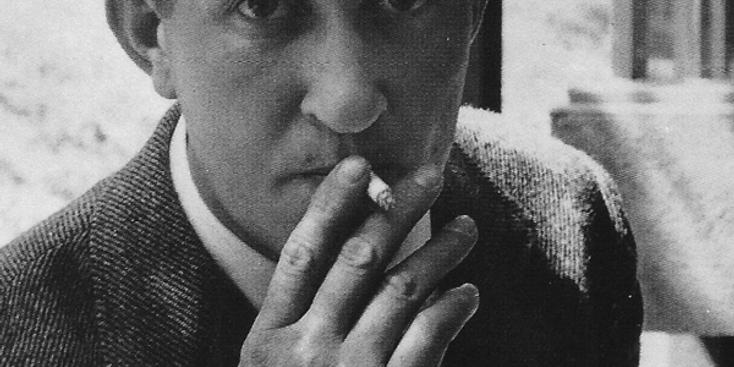

Craig Ellwood

Architect | 1922 - 1992

Charles ‘Chuck’ Bobertz and Gerry Miller hired Craig Ellwood (and Ellwood’s first associate - draftsman Ernie Jacks) in 1953 to design a home for a flat lot near San Diego State College akin to others in the series of early ‘wall houses’. In 1956-57, Craig Ellwood was the subject of a one-man show at San Diego State College, produced in part by local modernist architect Lloyd Ruocco.

BUY Craig Ellwood: Furniture HERE.

“Ellwood’s colloquially crude description captured the communicative power of his design: you put your ass to the street and you smile to the canyon,” – Alfonso Perez-Mendez (in Craig Ellwood, In the Spirit of the Time, 2003).

Between the 2000-2017 I owned a home that would be later rediscovered as Case Study House design Craig Ellwood's Bobertz Residence (1953). During my time in the home, I learned a great deal about Ellwood's life (in part through biographers and his daughter Erin), career (in speaking with his former staff and clients), as well as my own home's history (through interactions with the original client). Through it all, Modern San Diego was born, the house was restored and I left my ownership with a greater understanding of how people and building interact (the whole is greater than the sum of its parts). What follows is the history of how the Ellwood design, which was lost to a simple footnote for decades, came to be in the first place.

Charles ‘Chuck’ R. Bobertz was born on September 17, 1922, in Union City, New Jersey. Securing a degree from Middlebury College in 1946, Charles would meet his future wife, Gerry Miller, while at Cornell Business School, where he received his MBA degree in 1948. Gerry earned her B.A. in Fine Arts at Cornell that same year. Early in their relationship, she told Chuck (and later to his mother’s dismay), that at age 13 she had announced to her own family, upset with “snow up to my armpits,” that she was moving to California. Fine Arts studies propelled her towards seeking an architect who could design with “clean, modern lines.” These two motivations would help steer the young couple to the hub of West Coast modernism and one of its pioneering designers.

Chuck helped Gerry secure a job as editor for the New York State Department of Education in Albany while he was interning for Department of Health and Education. The sweethearts were married in Albany, New York in 1948. Shortly thereafter, Charles started working in Cornell’s financial offices (ca. 1949-1951). Gerry continued on with her studies earning a MS in Education. A lifelong passion for teaching began with early work experience editing “…pamphlets and books that went to teachers in New York State”. They begin saving money to move to California.

“…Life after World War II, was…difficult... People were re-building and trying to survive a difficult economy... For us [there was] no Brubeck, martinis, art shows, nor time… In our twenties we felt we had to get established financially. We had no help from our families, and arrived in California with little cash. I made $2,400 teaching and Chuck $3,500 at Cornell… We knew if we invested in knowledge we'd… achieve our goals. We were taking financial courses at all times (except during building the home). I also took courses in interior design, nutrition, modeling, and painting. Reading and studying were a big part of our life. Cornell Extension booklets: Time and Motion Studies: How far apart to place stove, and refrigerator, how to organize, simplify cleaning, shopping etc. We designed and had built our sofa and dining table in Berkeley, (long before we knew about Ellwood). I sewed and tacked the upholstery. We hunted and explored the best inexpensive table wine…,” Gerry Bobertz Franklin would later summarize the years immediately following World War II.

Landing first in Berkeley, California, Gerry’s rheumatoid arthritis flared up causing her to spend a week in the hospital while doctors tried to diagnose her ailment. After all, she "was too young for arthritis". During their time in Berkeley, they hired one of Gerry’s student’s father to design furniture present in early photographs of the Bobertz Residence (ca. 1956). Saving money, while investing in style, they contracted out for cost-effective furniture, and purchased other contemporary décor including Russell Wright’s latest dinnerware line.

In 1952 the couple moved to San Diego as Charles secured work at the County Health Department. Gerry arrived in San Diego on crutches on the advice to move, south and inland, where the weather would be dry. The newlyweds rented an apartment across from Point Loma High School at 2312 Chatsworth Boulevard. From this address Charles would start a meaningful, longtime friendship with Fred Mowrey. Gerry taught at Loma Portal Elementary and Ocean Beach Elementary schools.

Regular readers of John Entenza’s monthly, the young, educated couple (that architectural writer Esther McCoy would later term ‘progressives’) “…studied Arts & Architecture Magazine…where we found Craig and loved his work.” Gerry recalled contacting the publication to obtain Craig Ellwood’s phone number. Over the phone, Ellwood invited them to meet at his office. Interestingly, at the time, he was working from a back bedroom of 1811 Bel Air Road, the address of Case Study House 1953 while it was still under construction. “When we went up to see Craig, at his Westwood home, we discussed many of his homes with pictures, plans, etc.,” Gerry would remember years later. They hired him during that first meeting.

“Craig's indoor/outdoor approach hooked us; the way his walls continued from inside to outside... We also wanted floor to ceiling glass and a light, airy feeling. His clean lines and details: the black recessed strip where floor and walls met…,” Gerry would later summarize the many, varied ingredients that comprised Ellwood’s ethos.

Asking the architect to keep the budget at $15,000 they recognized that his numbers were based on Los Angeles prices – as he “…apparently knew nothing about the San Diego market... We were to be the painters, stainers, and to put flooring in to save money. I was to be the liaison between workers, contractor (whom I rarely saw), and Craig so I gave up teaching for two years. Craig was very pleasant but seemed stressed from handling so many projects,” recalled Mrs. Bobertz. The final assessed cost of building the home was $14,750 – after Ellwood wrote his draftsman Ernest ‘Ernie’ E. Jacks in October, 1953 that the project was running over budget at $16,900. Several items, including cabinetry and masonry work, were deleted during construction to bring the budget down.

The couple first bought a lot for $6,000 at 5832 Corral Way where they intended to put the home Ellwood was to design for them. At the time, the La Jolla neighborhood was absent houses, yet from where the house was to sit Chuck and Gerry could see “the ocean hugging the coast from Pacific Beach south to the Mountains of Mexico.” Shortly after purchasing the land and engaging Ellwood, a local contractor offered the cash-strapped couple twice the price. They sold the lot for $12,000.

Between March-August 1953, the Bobertz’s hired Craig Ellwood to build them a home for, what then was a vacant lot at, 5503 Dorothy Drive. Gerry Bobertz would later recall that Ellwood, who was primarily designing homes in the Los Angeles area, was essentially selling them plans. They would oversee construction on their own. During this time, the Bobertz Residence would be detailed by Ellwood’s first employee Ernie Jacks. “We never were told that anyone else worked on our plans. Craig gave us the impression he did them,” Gerry would later recall.

Jacks had moved to Los Angeles from San Diego after flying for the US Navy from the airfield on Coronado to work for Ellwood in January, 1953. The Bobertz Residence was detailed by Jacks, the (first and) only associate working for Ellwood at the time. Jacks only remained with him for 8 months (January-August). Shortly after completing the plans for the home (and a handful of other Ellwood projects), Jacks would leave Los Angeles to advance his education and to work for Edward Durrell Stone. Following the completion of his advanced degree, Jacks would begin a multi-decade career teaching at the University of Arkansas alongside E. Fay Jones, Edward Durrell Stone, Cyrus Sutherland and Charles Thompson.

With working drawings complete, Jerrold Lomax joined Ellwood as his second draftsman/associate, on September 1, 1953. He aided Ellwood in finishing the Bobertz Residence and other Jacks-initiated projects. By September 1953, the Anderson Residence was pretty far along – so the duo used it, in part, to prototype the Bobertz House. Lomax recalled the change order for the façade from brick masonry to tongue ‘n’ groove redwood was made on the job site when prices came in. Wood was likely a third less expensive than the masonry in the plans. The couple was on a tight budget and cuts were made.

Five decades later, the original client did not recall the details of any ‘change orders’ explaining the difference between Jacks’ extant plans and the as-built home. During the planning stages, Gerry Bobertz Franklin did recall requesting of Ellwood to move the house closer to the street to increase the backyard patio and pool area. Apparently, Ellwood was upset with the variation in the height of the roofline on the north façade – rather than demanding the contractor to make good on the issue, Ellwood reached a compromise with him. “Craig wanted his house neat, without any distractions to spoil the purity of lines,” Gerry would recall.

Mr. Lomax further recollected that Craig had a negative feeling about the house – if “he were really interested in the project he would have been more involved in process.” While Lomax did recall Gerry Bobertz calling the office, Craig did not have good communication with the contractor in San Diego and did not hire a supervising architect for contractor administration. “We phoned him nearly every evening during construction to keep him aware of progress or problems. He came down if there appeared to be a problem. He seemed to be keenly aware if things were going according to his plans. Incidentally, there were several plans before we all agreed to the final,” Gerry later recalled.

The Bobertz Residence would later be joined with other homes of this era by Craig Ellwood (and Associates) into a series later referred to as ‘Wall Houses’. Several of these homes were designed by Ernest Jacks during the short time he worked for Ellwood. Among these were the Kelton House (not built), Harrison House (not built), Coppedge House (not built), Anderson House (656 Hightree Road, Los Angeles), Froug House (not built), Case Study 17 (9554 Hidden Valley Road, Beverly Hills) and the Howard Steinman House (22476 Carbon Mesa Road, Malibu).

According to Jacks, he and Ellwood began work on designing the house. Towards the end of the project Jacks was working on the drawings solo - working from the back bedroom of Case Study #16 (AKA C.S.H. 1953) where they both lived and ran the architecture practice. Craig Ellwood would later write to Jacks, following his move to Arkansas mentioning problems with the Bobertz project – including the project going over budget.

Construction was said to have begun shortly after the drawings were complete – in August, 1953. While it remains unclear what date the couple took occupancy of the home (as they reportedly lived in the house while it was still unfinished), the County Assessor’s Construction Record states March 14, 1955 as the completion date. Their phone number, upon completion, was listed as Ju2-7421 in local directories. They lived in the house while it was still being finished – cutting costs by creosoting and staining wood as well as installing cork floors (in bedrooms, living room, hallway and kitchen) and asphalt tiles in both bathrooms themselves.

Chuck drove Gerry over to the property each morning where she set up a chair and table to oversee the daily progress of two older gentleman that made up the construction crew. According to Gerry, she served as the General Contractor on the project, while Charles travelled to his office daily. Craig Ellwood was reportedly made aware of the daily progress on the home as Gerry phoned him each night after supervising the effort. She later recalled that taking night classes in reading blueprints helped her stay on top of the workers.

“Craig had a dreadful time with contractors who had never before seen nor built that type of house,” Gerry commented. At one point Ellwood drove down to San Diego and told a contractor to remove the entire kitchen counter, which was installed incorrectly, and replace it. “He was a perfectionist and wouldn't accept less. He even brought a master plasterer from L.A. to do the work!,” recalled Mrs. Bobertz.

The interior furnishings were purchased locally, at Ilse Ruocco’s Design Center as well as custom made to Gerry’s specs by ‘skilled workers following my design or pictures… Craig sent us to a place in Los Angeles for Belgian linen drapes. Our cat loved them!,” Gerry would later recall. The interior hosted white unpainted plaster walls, lightly stained tongue ‘n’ groove redwood walls, Phillipine mahogany doors and several linear feet of masonite-pegboard sliding closets throughout the house. The pegboard material effectively allowed the closets to breathe. Regardless of the holes, visitors continued to peak in to see the contents of their closets. Though called for in the plans, the newlyweds did not install the accordian wall between the twin children’s rooms, instead using the space as one large(r) room. While the plans called for cabinetry in both the living room and laundry room, it was not installed in further cost-saving efforts. One signature item, Gruen Lighting’s "Finlandia", was a signature lamp installed over the dining table in Ellwood homes of the era. “It was super-expensive but we got it because Craig suggested it,” Gerry stated.

The architect also directed the owners to apply a light white-wash on the exterior redwood. “It wasn't flat gray but a light pink-gray with the grain showing… a very lively [color], not flat, gray or "battleship gray," Ellwood’s client would later remember.

Craig Ellwood suggested the young couple hire Eric Armstrong to design the landscape – one of several ‘extras’ the newbies went along with at the architect’s suggestion.

Born on February 1, 1922, Eric Armstrong would secure the 10th California State License to practice as a Landscape Architect. In 1954, while working from 1200 N. Beverly Glen, he provided a single-page landscape drawing for the Bobertz home – which included, though never installed, a shuffleboard court, pool, potting shed and outdoor cabinetry, as well as several unique plantings. Much of Armstrong’s plan was installed by Chuck Bobertz himself. Armstrong would later serve as the consulting landscape architect for U.C. Santa Barbara helping to develop the campus master plan in 1963. Armstrong’s California license to practice expired on February 29, 1992 and at that time his address was in Bandon, Oregon.

“Chuck and I followed the Armstrong plan as far as what we did accomplish. The last year I was there I planted flowers on the east back. We never fenced that side as the neighbors had a horizontal fence. (Craig couldn't have liked it as he wanted "all wood to be vertical as the tree grows"). We also had Armstrong's plan in the twin bedroom patio which added charm. The trees were gorgeous and the ivy made delightful shadows on the fence. The cat enjoyed it, also.”

Shortly after receiving the landscape plans, the couple were already planning to move the pool to the lower level to reduce the glare off the water reaching the house. “We didn’t get the pool in partly due to money- we hadn't planned to spend a small fortune on lights, drapes, etc. and the lot in La Jolla. Also we were weary of workmen who seemed so negative and independent. At that time, the post-war boom in tract housing made construction jobs easy to find.”

In the courtyard they followed the landscape plan; ivy around the concrete pad and koelreuteria trees. That area off the twin bedrooms would become a multi-purpose area for play, dining, and relaxation for themselves and guests.

The patio would become their favorite of Ellwood’s outdoor spaces around the home. The Bobertz couple hosted parties at home with their co-workers using the ‘children’s courtyard’ for the bar area – where alcohol was served.

During their time in the home (ca. 1956-57), Craig Ellwood was the subject of a one-man show at San Diego State College, produced in part by local modernist architect Lloyd Ruocco. This is reportedly among the 4 times Mr. Ellwood would visit the site while the Bobertz’s resided at the address – two of these visits Ellwood was accompanied by another man – potentially Jerry Lomax. A presentation on Ellwood’s work, just down the street failed to curb neighbors distaste for the house’s unusual stance. The County Assessor even called it ‘Ultra Modern’ following their inspection. The occupants often used the intercom system at the front door to eavesdrop on people talking about the house just prior to politely answering greeting them at the door.

In 1957, Gerry divorced Charles after her psychologist, Dr. Lockwood, diagnosed the couple as ‘incompatible.’ The stress of the building process initially led her to seek counseling. Believing, as many did back then, in the doctor’s prescription, the couple amicably separated. Charles took the 1946 Buick, which he bought new following the War, and bought Gerry a Volkswagen Beetle, and moved out. Gerry remained in the house until the fall of 1958. In November 1958, they accepted the first offer, selling the house for $29,000. “I was sorry to part with my baby -- I had put so much energy and time into it. However, my lifestyle had changed, my dates [often from military officer dances held at the Hotel Del Coronado] thought the drive was too far, and my activities were closer to the coast,” recalled Gerry Bobertz.

SOLD: Bobertz House by Craig Ellwood (1953)

SOLD: Bobertz House by Craig Ellwood

Between March-August 1953, the Bobertz’s hired Craig Ellwood to build

them a home for, what then was a vacant lot at, 5503 Dorothy Drive.

Gerry Bobertz would later recall that Ellwood, who was primarily

designing homes in the Los Angeles area, was essentially selling them

plans. They would oversee construction on their own. During this time,

the Bobertz Residence would be detailed by Ellwood’s first employee

Ernie Jacks. “We never were told that anyone else worked on our plans.

Craig gave us the impression he did them,” Gerry would later recall.

Architect

Craig Ellwood

Can't Miss Modern!

Sign up for our newsletter and get exclusive content from Modern San Diego.