Marjorie Marj Hyde

1924 - 1987

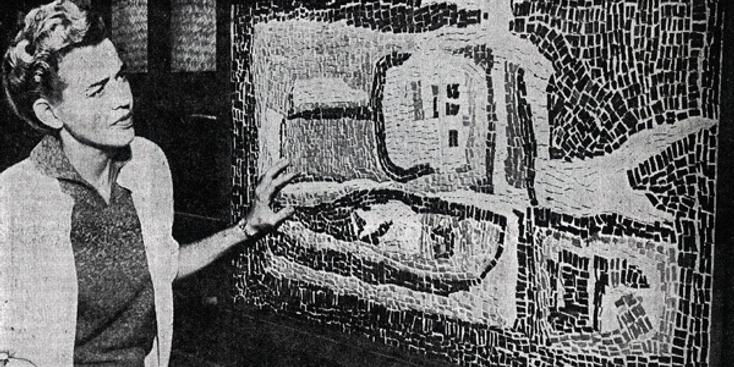

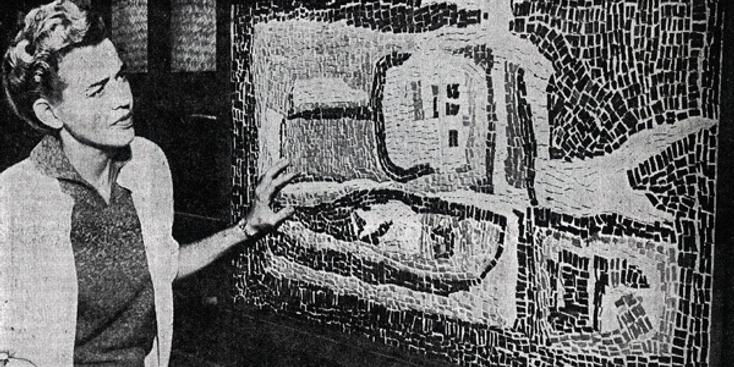

Born in Salt Lake City, Marjorie 'Marj' Hyde studied under Earl Loran, and Mrs. Peterson O’Hagan while at Cal prior to traveling in the US and Europe following World War II. Arriving in La Mesa in 1951 she started teaching at La Mesa and Grossmont High Schools. In 1956, one of her mosaics toured the nation in the 'Craftsmanship In A Changing World' exhibition.

Marjorie 'Marj' Hyde was born in Salt Lake City. According to Dr. Armin Kietzmann, as "...a young girl she was a romanticist, painting and drawing landscapes, still-life, and animals. During her high school years, which fell in the time of World War II, she painted the downtrodden, innocent victims of war in a heavy and compact style.”

She received her B.A. at either USC or Cal before securing her MA or MFA from Cal. She reportedly studied under Earl Loran, and Mrs. Peterson O’Hagan during her time at Cal (where Hans Hoffman and Clyfford Still had helped form the department prior to her arrival). “As a result of those years, she recognized that the relationship between the different values of colors, shapes and lines are more meaningful and better apt to express emotional and intellectual intentions than documentary or sentimental subjects,” according to Dr. Armin Kietzmann. Her work reflected the ideas of Cezanne and Matisse during these formative years.

Between 1946-1950, according to the Los Angeles Times, she pursued a career as an artist in Paris after World War II. Travelling extensively, the young painter stopped in the San Fernando Valley, Ravenna, Perugia and Rome before returning to Richmond where she began her path in teaching art at Contra Costa Junior College. Shortly thereafter, she relocated to a “…delightfully wooded house on Stanford Avenue…” [in La Mesa] and Grossmont High School where she started teaching in 1951.

Marj Hyde received national attention, in 1956, when one of her award-winning works, a mosaic, toured the nation with an exhibition called, “Craftsmanship In A Changing World,” put on by the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York.

Here in San Diego, Hyde's work caused a stir. The same year of the traveling exhibit, a group of Hyde’s “innocent, elegant” paintings were hung in the newly opened, Lloyd Ruocco designed, Security Trust and Savings Bank (on 4th and University) in Hillcrest, where they were supposed to remain for one month. Instead, the paintings came down after just two days, having provoked many complaints.

Writer James Britton’s June, 1956, Art of the City column documented the whole affair:

“If my kid painted pictures like those, I’d give him a beating,” said one customer. That’s only a sample of the intolerant reaction heard by officials of Security Trust and Savings Bank when their handsome new Hillcrest branch opened with innocent, elegant paintings by Marj Hyde on the wall.

How did the paintings get into the bank? It was architect Lloyd Ruocco’s idea, and he seems to have hypnotized bank officials with his sharply focused, insidious chatter about clean design, light design, bright design, right design. When it came time for the finishing touch of grace, Ruocco asked Miss Hyde to select paintings of hers that would complement his architecture. She understood they would hang for a month, after which another local painter of integrity would be dangled before the eyes of the money changing citizenry.

Bank officials may have been hypnotized, but they snapped out of it when the lowbrow complaints started buzzing in their ears. They quickly ordered the paintings taken down, though only two days had elapsed of the month Miss Hyde expected. Said manager M.A. Herbert: “Only three people made favorable comments on the pictures.”

Probably unaware that they were slapping a genteel young lady who happens also to be a passionately sincere painter, the bankers had proceeded naturally enough on the assumption that there is no profit in upsetting good customers. The thought could hardly have been expected to appeal to them, as it appeals to us, that a little upsetting is just what such customers need.

Why should bankers be expected to carry the torch for quality in art? The obvious answer is that bankers are recognized pillars of society, and pillars make fine support for torches.

Bankers often supported advanced art, even finding it good for business. American history boasts many banks that were pioneer architecture and architecture is the most abstract of arts. One of the celebrated building designs of the twentieth century’s sixth decade is the Manufacturers Trust Company (Fifth Avenue at 43rd Street, New York), which confronts its customers with many bold works of art, including Harry Bertoia’s mysterious sculpture and even a painting by – dare we say it? – Picasso. Its president H.C. Flanigan, is an avid collector of modern art.

President of San Diego’s Security Trust and Savings Bank is Mr. A. J. Sutherland, a widely respected community leader whose list of public stance is unsurpassed locally. Security’s downtown office, where Mr. Sutherland sits, is hung with reassuringly familiar landscape paintings to which no one could possibly object except some odd duck with an art educated eye in which case most of the landscapes would be pronounced esthetically dead on sight.

If Security’s official took one step forward and a dozen backward when they came face to face with the art of pure painting, we still can say to their credit that they are up to date in their architecture. In addition to the Ruocco walk-in branch, there is a delightful clean cut Security Drive-n Bank diagonally cross-corner at Fourth and University. The drive-in was designed by architect Selden B. Kennedy.

Miss Hyde’s well-bred paintings not in the least wilted by their turndown at the bank, can be see until June 10 in the magnificent foyer of the Capri Theatre. Capri owner Burton Jones, the outstanding San Diego businessman-connoisseur always has modern art on view. He finds that his customers mostly enjoy the gaiety of it all and seldom complain of pains. Moral: bipeds in the mood for entertainment are more likely to enjoy colorworks than those fearfully venturing forth to negotiate a loan.

For an Art Guild panel discussion, ‘Artist to Artist’, held on January 17, 1958, Ms. Hyde provided the following personal statement:

"I believe that the art of painting involves projecting life into inert material; this requires complete dedication and intensity to purpose. The life quality in a successful work comes from the artist and not from the subject, however worthy, and not from the material, however costly.

For me painting is a drama of form; a drama that is a product of emotion and thought. By this I mean that the drama, to be successful, must exhibit a high degree of control and discipline. Pure raw emotion may be therapeutic but is not necessarily of aesthetic value.

I believe the artist paints, not because he can, but because he must. And I feel that painting becomes a way of life that demands of the artist the development of a personal philosophy – the constant seeking of answers; a search for subjective reality, as the Orientals say.

In my own work I attempt to create something that looks “natural” so that if I am asked “What is it?” and I answer “A Painting”, the answer will be understood. Occasionally I feel that I have succeeded when the finished work has the look I call “The Ancient Future.”

I have been painting for ten years. Five years ago I resented any implication that my work was influenced by the work of others. Now I freely admit influences and am grateful for what I have learned from Cezanne, Paul Klee, Morris Graves, Martine, and of course from Picasso who tells us that “Nature is what we have, Art is what we want.”

In her classes at Grossmont College, Hyde encouraged students to spend time out of the studio, developing a sense of social awareness. "She was quite a dynamic personality," said sculptor David Beck Brown, a former student of Hyde's recollected. "She was very demanding. She encouraged students to be involved and participate. She's been a big influence."

Ms. Hyde was instrumental in establishing a permanent art collection for Grossmont College before her retirement in the summer of 1978. Besides working as an artist and teacher, Hyde published an illustrated book of her poems and devoted herself to promoting the welfare of American Indian students in San Diego County. She died in January, 1987, at the age of 63.

On January 20, 1988, the Grossmont College Art Gallery was officially renamed and dedicated the Hyde Gallery, in honor of its founder. An artist, teacher and former head of Grossmont's art department, Hyde believed that "Art must be a means of communicating with oneself and that communication then touches others.”

One Person Shows:

San Diego Trust & Savings Bank, San Diego (1956)

Capri Theatre, San Diego (1956)

Fine Arts Gallery, San Diego

Flea Market West, San Diego (November 17, 1963)

La Jolla Museum of Art (April 9- May 7, 1967)

Hyde Gallery, 'The Canticle Series' (April 23-21, 1978)

Retrospective Exhibition, Hyde Gallery (January 1988)

Group Shows:

San Diego Art Guild

Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York (1956)

Yavapai College, Prescott, AZ (May, 1970)

Resources:

Marjorie Hyde: ‘Why’ is the Vital Factor’ by Dr. Armin Kietzmann (October 16, 1965)

'The Mysterious Figure of Marj Hyde' in California Review (Fall 1963)

'Shekel and Hyde' (James Britton’s ‘Art of the City’, San Diego & Point

(June 1956)

'Art: A Moveable Feast' by Marilyn Hagberg (April 1967)

'Craftsmen of San Diego' in San Diego & Point

'Spotlight San Diego Arts' in Los Angeles Times (January 20, 1988)

Can't Miss Modern!

Sign up for our newsletter and get exclusive content from Modern San Diego.